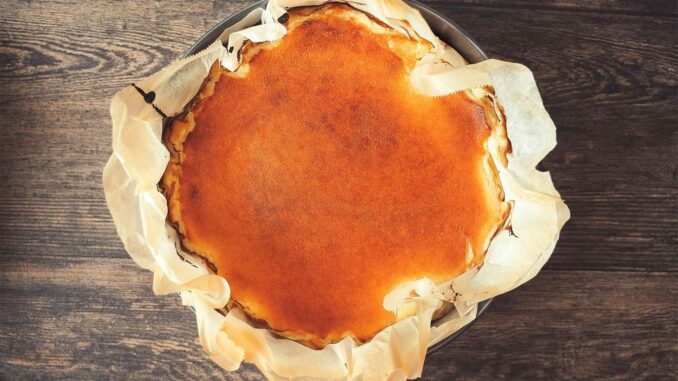

From San Sebastián to Paris feeds, Basque Burnt Cheesecake thrives on flaws, heat, and contrast—why a rough edge became a modern French-adjacent icon.

Basque Burnt Cheesecake was born in northern Spain, not France. Yet it sits comfortably in the French dessert conversation. The reason is not geography. It is attitude. The cake rejects polish. It favors heat, contrast, and visible imperfection. Its scorched top, custard center, and cracked edges photograph well and forgive mistakes. That combination has made it a favorite of home bakers and creators chasing authenticity. French pastry culture, long associated with precision, has also evolved. Contemporary Paris kitchens value taste over ornament and clarity over excess technique. Basque Burnt Cheesecake fits that shift. It uses few ingredients, short prep, and extreme baking temperatures around 240 °C (465 °F). It scales easily and travels well. On social platforms, it reads as honest and confident. On menus, it bridges cultures without apology. This article explains how the cake emerged, how it is built, why it spreads online, and why it feels French-adjacent today.

The origin story rooted in San Sebastián, not Paris

Basque Burnt Cheesecake was created in the early 1990s at La Viña, a small bar in the Parte Vieja of Basque Country. Chef Santiago Rivera aimed for flavor and speed, not refinement. The recipe used cream cheese, sugar, eggs, cream, and flour. No crust. No decoration. The oven ran hot. The top burned on purpose. The center stayed loose.

The cake spread locally, then nationally, then internationally. San Sebastián already had culinary gravity, with a dense concentration of acclaimed restaurants. Visitors tasted the cake and carried the idea home. By the late 2010s, it appeared in bakeries across Europe, the United States, and East Asia.

Calling it French is inaccurate. Calling it French-adjacent makes sense. The Basque region spans both sides of the border. Culinary exchange is constant. Techniques, suppliers, and chefs move freely. The cake crossed the border not as a copy, but as a concept.

The technique built on heat, timing, and restraint

The method is blunt and technical. Mix gently. Bake very hot. Stop early.

Most professional kitchens bake the cake at 230–260 °C (450–500 °F) for 25–40 minutes, depending on pan diameter. A common format is a 24 cm (9.5 in) round springform lined with parchment that climbs above the rim. The parchment wrinkles. That is intentional.

High heat triggers rapid Maillard reactions on the surface. Sugars caramelize. Proteins brown. The top turns dark brown to nearly black. Inside, the custard sets at a lower temperature. Pulling the cake while the center still trembles preserves a creamy core.

Cooling matters. The cake collapses slightly as steam escapes. The top cracks. The sides fold inward. Those changes create the “burnt” look. Refrigeration firms the center further, but many chefs prefer serving it at 18–20 °C (64–68 °F) to keep the custard supple.

This is not sloppy cooking. It is controlled imbalance.

The ingredient logic favors fat, water, and balance

Ingredient lists are short. Ratios matter.

Cream cheese provides structure and tang. Heavy cream raises water content and smooths texture. Eggs set the custard. Sugar sweetens and fuels browning. A small amount of flour stabilizes the cut. Salt sharpens contrast.

Typical professional ratios by weight for a 24 cm (9.5 in) cake:

- Cream cheese: 900 g (32 oz)

- Sugar: 250–300 g (9–10.5 oz)

- Eggs: 5 large

- Heavy cream: 450–500 ml (15–17 fl oz)

- Flour: 20–30 g (0.7–1 oz)

- Salt: 3–4 g (0.1 oz)

Vanilla is optional. Lemon zest divides opinion. Many purists avoid both.

The result is dense but fluid. Rich but not cloying. The burnt surface counteracts sweetness. Texture carries the experience.

The aesthetic that rewards imperfection and speed

Basque Burnt Cheesecake looks “wrong” by classical standards. That is the point.

The surface blisters. The edges buckle. The parchment shows. When sliced, the center may ooze slightly. On camera, these cues signal authenticity. They imply heat, risk, and immediacy. Viewers read the cake as honest.

Social platforms reward speed and repetition. This cake delivers both. Mixing takes minutes. Baking is single-stage. There is no water bath. There is no glaze. Failure rates are low. Variations still look intentional.

Creators can post cross-sections, jiggle tests, and cooling collapses. Each moment is visual. Each moment reinforces the brand of “perfectly imperfect.”

The French-adjacent adoption driven by modern pastry values

France did not invent the cake. France adopted it.

Over the past decade, French pastry has moved toward clarity. Chefs emphasize ingredient taste, seasonal sourcing, and reduced sugar. The Basque Burnt Cheesecake aligns with that shift. It avoids decorative excess. It centers flavor.

Paris bakeries often tweak the formula. Sugar levels drop by 10–15 %. Baking times shorten to protect the custard. Some versions use fresh cheese blends. Others adjust pan size for individual portions around 10–12 cm (4–4.7 in).

On menus, the cake sits comfortably beside tarts and choux. It feels contemporary, not foreign. Its Basque roots add credibility without demanding explanation.

The flavor profile anchored in contrast, not sweetness

Taste explains longevity better than looks.

The burnt top tastes bitter-sweet. The interior tastes milky and tangy. The mouthfeel shifts from firm edge to soft core. Salt amplifies everything.

Measured sweetness often sits around 18–20 % sugar relative to cream cheese by weight. That is lower than many New York-style cheesecakes. The reduction keeps the dessert adult and balanced.

Serving options remain minimal. Some kitchens add seasonal fruit. Others offer nothing. The cake stands alone.

The variations that respect the core idea

Innovation exists, but it is restrained.

Some bakers infuse smoke by briefly torching the top. Others add miso or browned butter for umami depth. Chocolate versions appear, though they risk masking the signature contrast.

What persists is the structure: no crust, high heat, early pull, visible collapse. When those pillars stay intact, the cake remains itself.

The economics that make it attractive to professionals

For restaurants, the cake is practical.

Food cost is predictable. Labor is low. Yield is high. A 24 cm (9.5 in) cake produces 8–10 portions. Holding time is forgiving. Waste is minimal.

Those factors matter in tight kitchens. They explain why the cake appears on both casual and fine-dining menus.

The cultural signal carried by a burnt surface

Basque Burnt Cheesecake signals confidence. It says the chef trusts heat and timing. It says flaws can be features. In a French-adjacent context, that message resonates.

French cuisine has always evolved by absorbing neighbors, then refining ideas. This cake was not refined into something else. It was accepted as it is.

That acceptance tells a broader story about taste today. Audiences value clarity over spectacle. They reward candor. A burnt top can be beautiful if it tastes right.

The cake will eventually share space with new ideas. It will not disappear. Its logic is too sound, and its message too current, to fade quietly.

Cook in France is your independant source for food in France.